Academy of Economic Studies

Faculty of International Economic Relations

Bachelor Paper

EMU and challenges implied by euro introduction

BG -

CP - Convergence Program

CZ

-

ECB - European Central Bank

EDP - Excessive Deficit Procedure

EU - European Union

EMI - European Monetary Institute

EMU -

European Monetary

ESCB - European System of Central Banks

FDI - Foreign Direct Investments

HU -

IMF - International Monetary Fund

LT -

NBR

- National Bank of

NMS - Non Member States

SGP - Stability and Growth Pact

The

European Union as it finds itself today is the result of the constant conflicts

that took place in

Well before the completion of the Single European Act there have been discussions related to the advantages that would come from a joining of forces from the major economic forces. This is when the notion of “convergence” was adopted by more and more economists that considered that member states should act more like each other so as to accomplish a development at their full potential.

Economic and monetary union was seen as the difficult but necessary and desirable next step in continuing to move forward. Initially, the aim was that the economic and monetary union (EMU) would be accomplished by the 1980s. The recession that was endured by the member states in the 1970s led to the stopping of the process, which restarted in 1978, but with a closer cooperation in what regards exchange rates, and was fully re-launched in 1988. It culminated with the completion of the first of three stages of EMU in 1990.

In that year, for example, the EU lifted the last of the remaining restrictions on borrowing money from one state to another, transferring money or investing in another EU country. From now on it was no longer necessary to fill in a form in order to obtain foreign currency for whatever reason such as going on holiday or studying in another country.

Furthermore, in the years that followed dividing lines were set between the finances of governments and that of central banks, thus putting an end to the ability of the governments to turn to the central banks for help in the case that they were not able to balance their accounts.

The three stages that were necessary for the creation and completion of the EMU (and that will be presented in the following pages) led to the need of several conditions and rules. First of all there were Convergence Criteria also known as the Maastricht Criteria. These are five essential conditions that have to be fulfilled by the member states in order to become part of the Euro zone area. Once part of the Euro zone area, member states have to channel their efforts to a continuous movement in the same direction by all, in order to achieve a sustainable growth. This is why a Stability and Growth Pact was needed.

The Stability and Growth Pact commits all EU countries to the principle of budgets that are balanced or nearly balanced. In other words, EU member states should not spend more than they earn. That way they can avoid the sorts of debt build-up which in the past have left governments either needing to increase taxes or short of money to spend on their citizens and on investment.

Since 1999, the year of its emergence, the Euro zone area established itself as a strong and stable economic power especially from a financial and monetary point of view. Still its weaknesses have been best revealed nowadays at the time of a global financial crisis. One of European Monetary Union’s (EMU’s) major problems has been the matter of the real economy. In this field, the introduction of the euro has not brought the expected results. The matters of employment, economic growth and also of price uniformization for the same products throughout the Euro zone area have been historically perceived as domains with the lowest rate of success. This problem re-emerges now, when economic activity is being restrained due primarily to the restrictions in credit access for both households and economic entities which ultimately lead to unemployment and lower levels of output.

In

this period of great trial for economies around the world, the Non Member

States (NMSs)[1]

are mostly far behind in completing the

This paper will first of all present

a short history of the EMU and its effect throughout history and the ECBs and

Eurosystem’s involvement and role during this time. Afterwards, in Chapter II

the advantages and disadvantages of the implementation of the euro currency

will be presented. The disadvantages are going to be presented throughout the

experience of five member states (

At the end of the 1960s, the European Union managed to achieve the

general aspects of custom union and launched the Common Agricultural Policy.

This set a suitable basis for the deepening of the integration process. The

events that took place in 1968 led to the unexpected increase of wages in

Still, the Werner Report has never been implemented in spite of the fact that the Economic and Monetary Union objectives had been approved. All the provisions contained in the Werner Report were interrupted by the set of economic convulsions related to oil prices that emerge in 1971, emphasizing between them the inconvertibility of the dollar. The result being that the European countries forgot the plans for the EMU, established in the Report. In spite of this, they did attempt to preserve a certain order in inter-European exchange movements, for which the Monetary Snake was created in 1972. The failure of the acting upon the Report is also due to the collapse of the Bretton Woods System. Even more, the stability of the exchange rates that characterized the beginning of the 1960s was obtained in an economic climate in which this stability was not directly linked to the sacrificing of some national economic policies. Inflation rates were low and practically the same in most of the member countries until 1973, and the unemployment rate was at a medium level. That is why there was no need for drastic fiscal and monetary policies; there were no major imbalances to correct. Even more, at the time, the movement of capital was reduced which bought time for the short term monetary policies.

During the Bretton Woods agreements,

the United Stated sold its gold at a price of 35 dollars per ounce. The member

states owned dollars which did not pose a problem as long as they could be

converted into gold. Problems arise when the total amount of currency owned by

the states over passed the quantity of gold held by the Federal Reserve. When

the price of gold on the private market exceeds 35 dollars per ounce, the

central banks are tented to change their dollars so as to buy gold at a lower

price outside the Federal Reserve. Due to the situation created, in 1971, the United

States suspend the convertibility of dollars into gold. In the months that

followed, there was an agreement signed at

In 1978, due more to political

factors than to economical ones, the creation of the European Monetary System

was negotiated. The idea of introducing a European Currency Unit instead of

coming back to the “snake” was a well debated subject. The common aim was

monetary stability. During the European Council at

In the mid 1980s,

The Delors commission 'completed' the internal market and laid the

foundations for the single European currency. European Economic and Monetary

Union were based on the three stage plan drawn up by a committee headed by

Delors (the Delors Report). Delors and his Commissioners are considered the

'founding fathers' of the euro. The plan was adopted at

The Delors Plan structured the establishment of the Monetary Union in three stages during a 10 year period , in the following way: the first stage intended the reduction of fluctuation margins between the currencies of the Members States. This stage started on 1st July 1990 when capital movement was liberalised through the excluding of exchange controls. The second step of this stage is represented by the Maastricht Treaty that is designed to bring a series of amendments. It is not a treaty in the proper sense but its importance comes from the fact that it introduced the terms and conditions for implementing the Single Currency and creates a set of convergence criteria. This treaty also includes three pillars. The main pillar revises the European Economic Community Treaty (EEC) and redefines it as the European Community Treaty (EC). The other two pillars comprise the external and security policies and also the cooperation in the field of justice and internal affairs. One of the most important aspects that is referred to in the Maastricht Treaty is the establishing of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) and of the European Central Bank (ECB). The Treaty states that the following article shall be inserted:

‘ARTICLE 4 a: A European System of Central Banks (hereinafter referred to as ‘ESCB’) and a European Central Bank (hereinafter referred to as ‘ECB’) shall be established in accordance with the procedures laid down in this Treaty; they shall act within the limits of the powers conferred upon them by this Treaty and by the Statute of the ESCB and of the ECB ( hereinafter referred to as ‘Statute of the ESCB’) annexed thereto.

The treaty came into force on the 1 November 1993. Soon after this, on

the 31st December 1993 the first stage of the EMU comes to an end.

It also introduces the preconditions necessary for a MS to comply with so that

to become part of the EMU. There is no legal constraint on the MS regarding the

date they have to implement the common currency. Only

The second stage meant to totally liberalize the capital movements with the integration of the financial markets and, in particular, of the banking systems enters into effectiveness on 1 January 1994 until the 31st December 1998. The European Monetary Institute is established as the forerunner of the European Central Bank, with the task of strengthening monetary cooperation between the member states and their national banks, as well as supervising ECU banknotes. In 1995 the name of the currency and also the duration of the transition periods are established. This ultimately leads in 1997 to the European Council decision of adopting the Stability and Growth Pact designed to ensure budgetary discipline after creation of the euro. One year later in 1998, according to the specification of the Maastricht Treaty, the ECB is created and on 31st December 1998, the conversion rates between the 11 participating national currencies and the euro are established thus bringing to a successful end the second stage of the EMU.

Finally, the third stage irrevocably

fixed the exchange rates between the different currencies. This process is

still in progress. From the start of 1999, the euro is now a real currency, and

a single monetary policy is introduced under the authority of the ECB. A

three-year transition period begins before the introduction of actual euro

notes and coins, but legally the national currencies have already ceased to

exist. In 1992 the euro banknotes and coins are introduced and thus leading

throughout the following years to the widening of the Euro zone area, as

The European Currency Unit was compound of a basket of member states currencies and the weight, that each had on determining the European Currency Unit, was established according to the GDP level of each country and of trade. The fixed character of the exchange mechanism was insured by the determination of a central exchange rate between each currency and the European Currency Unit. The fluctuation margin was of ± 2,25%. The basic institutional and operational determinants of the European Monetary System have not suffered major alterations during the period 1979-1993 in spite of the changes that took place at European and international level. In 1992-1993, the system was subject to different challenges derived from the appreciation of different currencies, the unification of Germany, the doubts concerning the capacity of the system to cope with the new demands that were a result of the Maastricht Treaty concerning the European Union, the weakness of the US dollar, and from the pressure of more and more volatile currency market. Due to complications, in 1993, the fluctuation margins are increased from ±2,25% to ± 15%. The next 6 years actually represent the second step in the process of going from the European Monetary System to the Economic and Monetary Union that was focused mainly on the free movement of capital. It is also now when the group of eleven countries that were going to participate to the third phase: the actual introduction of the single European currency. The creation of the European Central Bank which is responsible with the monetary policy was preceded by the creation of the European Monetary Institute.

This institution has as main task to co-ordinate monetary policy of the central banks of the MS within the ESCB and to prepare the third stage of the EMU. This started in 1999 by the renaming of the EMI and transforming it into the ECB.

Along with the entering into effectiveness of the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union, the European Central Bank replaced the European Monetary Institute in 1998, thus establishing the main institutional frame of the union. Since January 1999, it has been showing its full potential in the stabilizing of The European Central Banks System (composed out of the European Central Bank and the national banks). Both of them have been established according to Art. 4A of the Treaty regarding the European Union.

Traditional financial institutions, such as banks and brokerage firms on capital markets, have changed greatly from their acknowledged structure, acting towards the increase of their activity across borders and towards remarkable mergers, thus creating hybrid institutions, which are active on various markets. Some specialists even state that part of this type of institutions have got even to the point where they modified the role of finances in world economy. Within these movements and world changes, the finances ministries, financial institutions and the capital markets regulators have become the most important surveillance and control institutions and levers, especially in what regards capital movements.

The creation of the ECB came as one major moment in the middle of this period of great economical change. Even though this institution with a unique statute covers only a limited number of members and it focuses its activity on a certain geographic region, ECB can integrate in the group of international powerful financial institutions such as International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), or that of the central banks. The activity of ECB can be divided into two categories. The first one is represented by the public institutions of the member states, members of the ECBS, EU bodies and a few basic international institutions that undertake similar activities related to the global financial system (such as those mentioned above). The latter includes the European business and financial communities and a certain groups of European civil society. Reality certifies that European public institutions extend the support represented by ECB and actively contribute to the success of this institution.

A central bank undertakes the task of a permanent analysis of the major changes that take place within the national economy, trying through specific methods to neutralise the negative influences and consequences of these. One of the main objectives of the ECB is that of guaranteeing and maintaining price stability. The ways in which this can be done may differ from country to country, no central bank being able to have the full set of correct answers. The objective of price stability demands for the monetary policy to be generally oriented beyond immediate effect that it can have over the economy. This effect is considered to identify with a time span of 2-3 years.

Bankers consider that the determining of prices can be taken into consideration when the inflation rate is not the basis for business decision-making. The interest for the stabilization of prices on the long run does not mean that the monetary authorities can ignore the short term effects of economic activity. One aspect that has to be acknowledged is that we cannot eliminate all the sources for potential inflationist shocks. This applies even in the case of a maintained price stability that has a predictable trend. Monetary policy alone will not be able to take the national economies to the expected level.

For example, shocks of offer that influence the level of prices with an accelerated rhythm of growth can occur at any given time. In this case, a monetary policy with the main objective of price stabilization will not have to take rash actions, the best solution lying in applying gradual solutions to reduce the level of inflation in time, during the adjustment of the economy to the relative prices.

Under the EC Treaty, the ESCB is entrusted with carrying out central banking functions for the euro. However, as the ESCB has no legal personality of its own (unlike the ECB and NCBs of the 27 EU Member States), and because of differentiated levels of integration in EMU, the real actors are the ECB and the NCBs of the euro area countries. They exercise the core functions of the ESCB under the name “Eurosystem”. This term has been adopted in November 1998. [6]

The European Central Banks structure is composed out of three decision-making bodies which also control the European System of Central Banks. The structure of the European Central Bank was created based on the model of the German Bundesbank. First of all there is the Governing Council that decides in matters which concern the monetary policy. The Executive Board is the management institution. It is also in charge of the implementing of the decision taken by the Governing Council. As long as there will exist European Union Members that are not part of the Euro zone area, the General Council is not going to be dissolved. This body is helping the non-euro countries cope with transitional issues that appear in the process of implementing the euro.

In what regards the European Central Banks System, it has as main objective the stabilizing of prices. It supports the general economic policies of the Community, thus contributing to the achievement of the Communities objectives by favouring the efficient allocation of resources. The main tasks that have to be fulfilled by the European Central Banks System refer first to the implement of the monetary policies adopted by the Governing Council of the ECB, secondly to undertake foreign exchange operations, to hold and administrate the Member States official reserves. The forth task of the Eurosystem is to promote an efficient payment system. Even more, it contributes to the conducting of the financial supervision: advices legislators in its field of competence and it compiles monetary and financial statistics.

NCBs have legal personalities

separate from that of the ECB, in spite of the fact that they are an important

part of the Eurosystem. Under the law of their country, they operate according to the guidelines provided

by the ECB in order for the Eurosystem to accomplish its tasks. Below are

presented the 27 members of the Eurosystem. Until January 1st 2007

when

The Eurosystem NCBs have transferred foreign reserve assets to the ECB totalling some €40 billion (85% in foreign currency holdings and 15% in gold). In exchange, the NCBs have received interest-bearing claims on the ECB, denominated in euro. Eurosystem NCBs are involved in the management of the ECB’s foreign reserves: they act as agents for the ECB, in accordance with portfolio management guidelines set by the ECB. The remaining Eurosystem foreign reserve assets are owned and managed by the NCBs. Transactions in those reserve assets are regulated by the Eurosystem. In particular, transactions above certain thresholds require prior approval from the ECB.[9]

Figure 1.1 – European System of Central Banks

The capacity of monetary policy to ensure price stability over the medium term is based on the banking system’s dependence on money issued by the central bank (known as “base money”) to:

meet the demand for currency in circulation;

clear interbank balances;

meet the requirements for the minimum reserves that may have to be deposited with the central bank.

Essential for the development of the euro zone member states is a good communication between the ECB and NCBs. Price stability and economic growth can only be reached by an effective monetary policy that is applied to a convergent area so as to not create disparities.

The decision of introducing the Euro was taken by the European Monetary Institute on 15th July 1997. In order for the introduction to be possible, a codified symbol was needed. The creators used the Greek letter Epsilon and the first letter of the word “Europe” crossed by two parallel lines that are meant to express stability and thus leading to the euro symbol (€). The name “euro” was decided upon two years earlier in 1995. It was launched on the 1st January 1999. At first, the euro currency was designed to be only an electronic currency used by banks, foreign exchange dealers, major companies, and stock markets .

In May 1998 the European Union selected the countries that were to become the first to implement the euro based on their ability to comply to several required criteria (“Convergence Criteria) and also, in December 1998 the Council of the European Union decided upon setting the conversion rates for one euro.

These convergence criteria were established in 1992 and they related to: inflation, budget deficit, national public debt, long term interest rates and finally, the national currency exchange rate. First of all, the inflation is supposed to be of no more than 1.5 percentage points above the average rate of the three EU member states with the lowest inflation over the previous year. Inflation performance should also prove to be “sustainable”. Secondly, the national budget deficit should be at or below 3 percent of gross national product. The national public debt should not exceed 60 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). A country with a higher level of debt can still adopt the euro provided its debt level is falling steadily. Actually, the assessment of fiscal sustainability in the case of excessive deficit procedure is meant to establish whether the budget deficit ratio “has declined substantially and continuously and reached a level that comes close to the reference value” or that “the excess over the reference value is only exceptional and temporary and the ratio remains close to the reference value”. The third Maastricht criteria is related to the long-term interest rates that should be no more than two percentage points above the rate in the three EU countries with the lowest inflation over the previous year. Finally, the national currency's exchange rate should have stayed within certain pre-set ERM-II margins of fluctuation for two years prior to entry in order for the member states to adopt the single currency.

These countries were:

The

The euro entered into circulation in

2002 and until that date, one year earlier,

The introduction of the euro automatically meant the renouncing to sovereign monetary policies and changes in the nominal prices as a means of adjusting prices between countries.

There

also is the legal aspect relating to the EMU. An ECB publication[15]

says that: “In theory, it would have been possible to conclude a separate

Treaty on EMU as a fourth pillar of the European Union; this approach was

considered in the early stages of the IGC negotiations on EMU36 but eventually

rejected. Instead the legal foundations of EMU were enshrined in the EC Treaty,

thus expanding the competence of the

A new exchange rate mechanism, ERM-II, entered into force at the start of Stage Three of EMU. It replaced the European Monetary System, which had played an instrumental role in the move towards EMU (see Section 1.1.2) but had to be adjusted to the new environment created by EMU.

ERM-II is an intergovernmental arrangement which is based on two legal documents:

• Resolution of the European

Council on the establishment of an exchange-rate mechanism in the third stage

of economic and monetary union,

• Agreement of 1st September 1998 between the European Central Bank and the national central banks of the Member States outside the euro area laying down the operating procedures for an exchange rate mechanism in stage three of Economic and Monetary Union, as amended by the Agreement of14th September 2005.

The purpose of ERM-II is to link the currencies of the Member States outside the euro area to the euro. The link is established by mutually agreed, fixed but adjustable central rates vis-à-vis the euro and a standard fluctuation band of ±15%. (see Annex 1: Central Parity of the European Monetary System). Narrower fluctuation margins may be mutually agreed if appropriate in the light of progress towards convergence.

The issue of whether the introduction of the European single currency is mostly beneficial or costly for the member states is still open for discussions as this subject is viewed from a subjective point of view. The process of European monetary integration is the subject of many books that talk about aspects such as effects, conditions, advantages and disadvantages of the monetary union.

From an international point of view, in the matter of business, decisions taken at some point that seem to be profitable actually end up showing a deficit due to exchange rate modifications. The less predictable the exchange rates, the more risky are the foreign investments and the less probable is that these companies will obtain a growth on foreign markets. The euro, through the fact that it completely replaces currencies such as the franc or the deutschemark, ultimately completely eliminates the exchange rate risk. Therefore, this will be an advantage for international investments in the Euro zone area. The exchange rate risk is potentially unpleasant for any consumer, producer, distributor or investors that take forward decisions. Unfortunately this describes the majority of the economic activities. The foreign direct investments had to benefit from the point of view that their value represents now one third of the Euro zone area GDP compared to just 20% ten years ago. This growth is mostly due to the implementation of the euro. This also has as consequence the increase in efficiency and competition.

One of the key advantages that the EMU brings is the ensuring of macroeconomic stability. The firmness with which ECB has implemented its policies aimed at sustaining the stability of prices in the Euro zone area, led to the consolidation of the general trust in the euro and to the creation of the basis for a sustainable economic growth.

Another positive aspect is related to the introduction of the single European currency is the fact that financing costs have declined to the advantage of both the private economic parties but also for the governmental ones.

The Euro zone area member states have the advantage of being protected to some extend by the resistance of the euro against the possible economic shocks that may arise in time. One example is the financial crisis that is experienced throughout the world.

The implementation of the euro brought the intensification of trade within the Euro zone area and now one third of the Euro zone area GDP is represented by the commercial trade between member states, compared to ten years ago when it represented a fourth.

In relation to the financial markets, the euro led to the complete integration of the interbanking monetary markets, and also to a deepening of the security markets (mostly stocks and bonds).

Furthermore, another positive aspect related to the euro is the fact that it strengthened the European identity in the world, more than half of the citizens of the Euro zone area consider that the EU identifies with the euro. The European currency has become the second international currency in the world. In spite of the fact that many Asian countries do not disclose statistics related to the composition of their national reserves, the euro represents approximately one quarter of the international reserves. Even more, it is the second currency in the world being used in 37% of the international currency exchanges. Having in mind the perspectives of enlargement of the Euro zone area, the euro will become the currency of the largest economic area in the world. The currencies of which the reserves are composed of are used by the central banks, governments and private companies throughout the world as a long term value deposit and so as to meet their continuous financial requirements. Historically speaking, only those currencies that are the most liquid, stable and that are accepted as means for payment within a large economic area have the potential of becoming important currencies in which reserves are made.

The euro also offers a series of indirect positive effects.

These benefits are directly related to the thorough changes in the behaviour of the financial markets and of the companies and therefore, they are controversial. Some of these are: macroeconomic stability, reduced rates of interest, economic growth and the structural reform.

The

ECB is created after the example of Bundesbank, which is known for the fact

that it is a highly independent bank. This might come as a disadvantage for the

countries with a low rate of inflation (

As

the euro reduces the inflation, it also puts pressure in the sense that it help

to decrease interest rates. Investors are willing to buy bonds only if they

know that the money that they are going to receive in the future will determine

a rate of income above the inflation rate. Therefore, investors demand

diminished interest rates or “inflation premiums” from the countries that enjoy

a higher price stability. This is a very important aspect for the countries

that have had problems in the fight against inflation (for example

Euro

implies a lower inflation rates and by the reduction of the rate of risk for

the foreign exchanges. For example, in May 2009 the annual inflation rate for

the Euro area was of 0.0% while for June, estimates predict that it will be of

0.1%.

In the past, an investor from

It

is considered that the euro aides the structural reform that is needed in

This

type of measures has raised fundamental questions on the topic of the long term

fez ability of the public and social expenses which are well known for the

proportions they can take. They have led to significant budgetary cut backs and

have brought a great attention to the importance of a sustained economic

growth. The budgetary restraints in countries such as

In spite of the fact that the euro seems to have only advantages, it also presents some less positive aspects. Still, there seems to be no clear balance between the two: advantages and disadvantages. This is more likely to be a subjective aspect, according to each government’s monetary and fiscal agenda. For governments the question of joining the Euro is a trade off on having higher unemployment and low inflation or lower unemployment with higher inflation; while some governments see price stability as their main objective.

Most of the disadvantages faced by the members of the euro zone are connected to costs. For example, the transition costs incurred by such an investment have never been seen before. These costs are felt by both institutions but also individuals. They represent planning and organising costs that will not be paid off only by the NCBs, but a certain amount will be left to the economic agents. For example: costs of adjusting invoices, bank accounts, databases, software, office forms and price lists. In addition, there were hours of training necessary for employees, managers, and even consumers.

Furthermore, the costs include the loss of independent monetary policy, which mostly means the loss of interest rate setting power and the loss of the possibility of exchange rate movements. In the case of asymmetrical economic shocks, as opposed to before it has adopted the single currency, the euro zone MS will not be able to tackle the situation through national monetary and fiscal policies. With their own national currencies, countries could adjust interest rates to encourage investments and large consumer purchases. Even more, the MS would have been able to devalue their currency in an economic downturn by adjusting their exchange rate. Through this, purchases of national products would be encouraged and thus lead to the needed equilibrium in the economy. Government spending is also a tool used by the NMS. such as unemployment and social welfare programs. In times of economic difficulty, when lay-offs increase and more citizens need unemployment benefits and other welfare funding, the government's spending increases to make these payments. This puts money back into the economy and encourages spending, which helps bring the country out of its recession. Some of the tools available after becoming part of the EMU are fiscal adjustment, labor mobility, capital mobility and fully integrated common financial market in the EMU.

One major disadvantage for the

There is also the actual cost of the coins and banknotes that has to be taken into consideration, even though this is not as important as the other disadvantages.

Another risk that is assumed by the euro zone MS is that of political shocks. They may arise due to the fact that there is one single voice speaking out for all the MS which could lead to tensions within the group. There is also the aspect of one member country financially collapsing which would lead to a chain reaction of adverse reactions all throughout the EMU.

Having in mind the numerous

layers of bureaucracy throughout

The euro has been created in order to bring stability and prosperity to the member states that become members of the EMU. Still, due to the fact that member states lose control of the monetary policy, the process of stabilizing the economy while facing shocks becomes harder. In normal circumstances, countries also have the power of using fiscal policies in order to react to any shocks. The ECB sets the interest rate throughout the euro zone area according to the general current conditions. Still, as conditions differ from one country to another, changes in the interest rate affect differently countries in different areas of the euro zone. A reasonable convergence of the monetary policy transmission mechanism across the euro zone members is what could stop the rise of strains and inefficiencies.

Best

suited as example are the experiences of

Since

its accession to the EMU,

One of the most important

benefits is the increase in credibility that

A similar situation has been

experienced by

In the case of

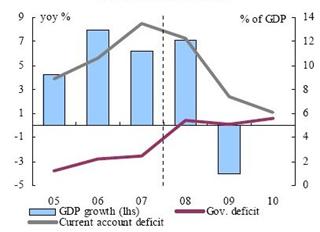

Figure 2.4.1.: Government Deficit as a Percentage of GDP

In the case of

In the matter of

US

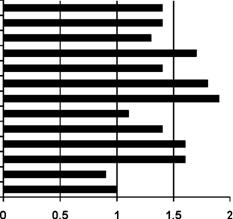

Figure 2.4.2.: Product Market Regulation

In

spite of the fact that the common currency has been partly blamed for the

economic slowdown and the tensions within the EMU that has been felt even since

the year 2003, the euro brought stability and had a general beneficial impact

on the poorest and less stable countries that adopted the currency. Convergence

for

Furthermore, between 1999 and 2007, the average growth of

GDP in countries such as

The slow progress made by the EU with the euro in its attempt to integrate economies is reflected in the fact that there is no real economic convergence in the eurozone. Only if the efforts of member states governments intensify their efforts in achieving convergence, if not, the economic divergence will deepen, putting strain on the system. Even more, as Daniel Gros mentions in the 2005 Report of the “Centre for European Policy Studies” Macroeconomic Policy Group, a combination between harsh initial conditions, declining economic fortunes and most of all, wrong policy choices have brought this situation upon the EMU.

This is not only a problem that arose with the deepening

of the current financial crisis. After becoming part of the euro zone, the

economies have diverged. For example in 2004, eight of the twelve member states

still did not meet the criteria and six of them (

Specialists

warn that the current financial crisis will speed up the process of divergence.

Some sceptics even take into consideration the possibility of member states

leaving the eurozone.

But this is less likely having in mind the current situation. One interesting

aspect is that there have been historical precedents. One of the most known is

that of

In spite of the fact that the EMU has encountered a slower development than expected initially, in the first ten years, the euro zone economic growth has averaged around 2.2% and the inflation rate around 2.1%.

Specialists have come up with four possible scenarios for the euro in 2015.

The first one presents the situation of a long-term success, where the euro implementation fulfills all economic expectations and leads to economic growth, financial stability and low inflation. This is the desired scenario by the leaders of the EU, the European Commission and the public opinion. Still, these expectations view the euro as being invulnerable, which is exactly the opposite of what it proved to be, especially now, in the time of crisis.

The

second scenario presents the euro exiting from the crisis although with great

difficulty.

Another possible outcome is a more negativistic one. The lack of a common political project would lead to the failure of the attempt to exit the crisis successfully. The EMU member states would face a loss of competitiveness, higher unemployment and growing inequalities between states will ultimately lead to making impossible a social dialogue. The attempt of the governments will be represented by a drastic reduction in social security deductions. This will be rejected by the public and this will lead to years of instability until communication and equilibrium is found. Specialists consider this to be the most probable outcome.

The

last situation in which

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) is part of the third stage of the EMU which began on 1 January 1999. Its main objective is to ensure that the Member States maintain budgetary discipline after the single currency has been introduced. The SGP actually comprises a European Council Resolution and two Council Regulations. It lays down detailed technical aspects regarding the surveillance of budgetary positions and the coordination of economic policies and the latter on implementing the excessive deficit procedure, for example.[42]

The origin of the SGP stands in the “Stability Pact for Europe”, an initiative launched by the German Government that reflects the concern for stability as expressed by their authorities before and during the negotiations of the Maastricht Treaty which was also reflected in the position of the Bundesbank. Actually, this had as one of the main purposes the reassurance of the German public that the euro will be as stable as the Deutschmark. The Pact received its current denomination in December 1996, during the European Council of Dublin.[43]

In June 1997 the European Council adopted the SGP, which complements the Treaty provisions and aims to ensure budgetary discipline within EMU. A mentioned above, the Pact consists of three instruments: a European Council Resolution and two Council Regulations. It was supplemented and the respective commitments enhanced by a Declaration of the Council in May 1998. The Member States implemented policies to fulfil the economic “convergence criteria” (Article 121 of the EC Treaty) and revised extensively their national legislation to bring it into line with the requirements of legal convergence (Article 109 of the EC Treaty). The adaptations concerned in particular the legal and statutory provisions for their central banks with a view to their integration into the Eurosystem.[44] Finally the SGP entered into force in 1999.

After

1993 when the deficit ratio of the euro was diminished to 3%, some euro area

countries have succeeded in maintaining progress with fiscal consolidation. But

in a number of others, fiscal consolidation has either stalled or even gone

into reverse.

The SGP contains provisions that determine the preparation of annual stability programs by euro-area MS meanwhile other EU MS prepare convergence programs and submit them to the Commission and the Council normally by 1 December of each year. The aim is the insurance of a more rigorous budgetary discipline through coordination and surveillance.[46]

The Council examines the programs at

the beginning of each year and delivers an opinion on each

are the economic assumptions realistic,

does the medium-term budgetary objective in the programme provide for a safety margin to ensure the avoidance of an excessive deficit and is the adjustment path towards it appropriate?

are the policy measures sufficient to achieve the medium-term budgetary objective?

what risks does the ageing of the population pose to the long-term sustainability of public finances?

are the economic policies consistent with the broad economic policy guidelines?

Still, there is one main issue regarding the SGP, which can be felt all around the world. In the context of the current global crisis, the SGP stimulates pro-cyclical fiscal policies. For example: in the case that a country enters into a recession period, SGP promotes restrictive fiscal policies. This means low budgetary expenses and that a high taxation level is imposed. This in spite of the fact that such a period in the economy of a country requires exactly the opposite of what the SGP promotes: the state should intervene for stimulating the aggregate demand through high budgetary expenses and a low taxation level. For avoiding these contradictions in period of crises, the SGP should be suspended in case of extraordinary circumstances in the global economy.[48]

Since its coming into being, the SGP has been often criticized. The peak was reached in 2002 when Romano Prodi, the European commission president at the time, described the SGP as being “stupid”. When he was called before the European Parliament to explain his reaction, Mr. Prodi defended his criticism of the pact, saying it was too inflexible at a time of economic slowdown. In spite of this, his solution for the situation was to give the commission more power to enforce the pact.[49]

Still, the pact has some advantages[50]. For instance, both inside and outside the euro area, the EU has seen a strong convergence in inflation rates, and the

data show that inflation is now low across the EU and exhibits few signs of any

resurgence. Furthermore, volatility in the real economy has declined, though

towards steadier but lower growth rates. The SGP also sustained the budget discipline – the EU policy was

restrictive but still, less risky than that of the

The Finance Ministry says in its document that it is estimating prudent developments in pay in the medium term, commensurate with the developments in productivity, and revenues from income taxes levelling off at 3.6 % of the GDP in 2011. The aggregate Government deficit in the first three months of 2009 stood at 1.5 % of the GDP, compared with a balanced budget in the first three months of 2008. The negative developments were the result of a fall by 0.8 percentage points in the aggregate Government revenues, from 8 % of the GDP in March 2008, to 7.2 % of the GDP in March 2009. The aggregate Government deficit was 1.9 % of the GDP in the first quarter of 2009, but the local administrations reported a surplus of 0.4 % of the GDP.

The entry preconditions that the NMS have to comply with before adopting the single currency are specified in the Maastricht Treaty. They basically require MS to achieve a high level of sustainable nominal convergence before participating in the EMU. The assessment is done every two years or at the request of the MS based on reports prepared by the EC and ECB. These preconditions have been presented in Chapter I.

The main aim of the revised edition of the CP released by the Ministry of Public Finances is to switch to the single European currency in 2014. The Romanian Government’s medium-term economic strategy aims to preserve macroeconomic stability, continue deflation, adjust the Government deficit and the current-account deficit to levels at which their financing becomes sustainable, protect the social categories that are the worst affected by the ongoing economic crisis, improve predictability and performance in the medium-term fiscal policy, maximize and improve efficiency of the use of European grants, earmark public money for public investments in infrastructure as an alternative source for job creation, secure long-term sustainability of the public finance, and also to improve efficiency of the public administration.

The latest report prepared by the European Commission as a response to the Convergence Programme 2008-2011 presented by the Government of Romania highlights ever since the beginning the fact that, even though the current “unprecedented global financial crisis” has affected many EU countries often leading to a strong deterioration in both the deficit and the debt positions, Romania showed a “lack of fiscal consolidation efforts when economic conditions were favourable”. Accordingly, the budget deficit that developed is due mostly to “overall weak budgetary planning and implementation”.[54]

The Maastricht criteria specify that a budgetary deficit due to extraordinary circumstances and with a few decimals over the 3% ceiling will not lead to the launching of the budgetary deficit procedures as long as this situation can be remedied in a short period of time.

Whenever the budgetary deficit of a country is above 3%, the Commission is required by the SGP to prepare a report, in which the reasons for the breach of the reference values are analysed. This analysis is based on the economic background and all the other relevant factors. Actually, the 2005 amendments brought to the SGP wish to ensure that the economic environment and the budgetary background have been well analyzed and taken into consideration. Thus, in case of an EDP, right measures can be taken in order for the MS to receive the adequate attention for the situation that it faces and therefore, to resolve the issue as efficient as possible.

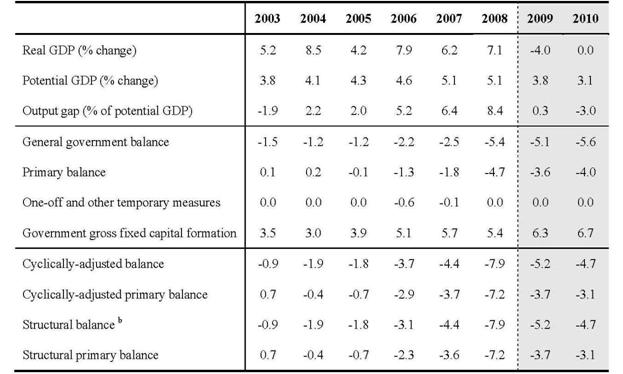

In its analysis, the Commission calculated the expected general governmental deficit for both 2009 and 2010. According to this, the deficit is expected to reach 5.1% of GDP in 2009 and 5.6% in 2010. The aim of the Romanian Government is to at least maintain these targets if not do better and by 2011 to reduce the deficit below 3%. This projection is based on GDP growth of -4.0% in 2009 and 0% in 2010 while IMF estimates that in 2011 the Romanian economy will recover through an estimated growth of 5%.

Recently,

IMF has started considering preparing a new macroeconomic scenario for

Recently,

IMF has started considering preparing a new macroeconomic scenario for

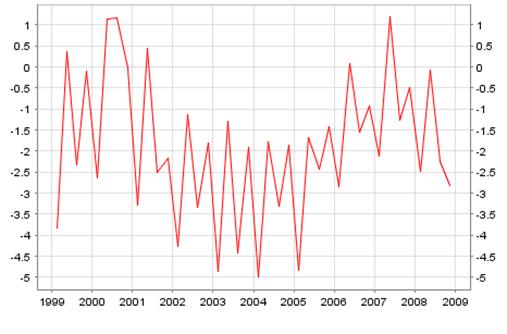

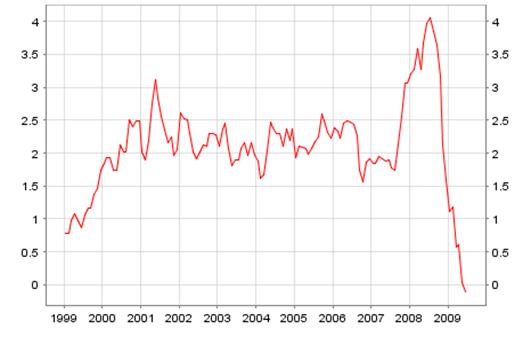

Graph

3.1.

–

Source: “Spring Forecast[55], March 2009

Consequently, in the case of a 7-8% decrease in GDP, the deficit will have to continue growing.[56] Still, the Prime-Minister Boc has announced that the increase in the budgetary deficit will be due to spending solely in the field of investments.

Another

major problem for

This was triggered by the actions and decisions that took place in the American subprime market. One of the most important reactions take to respond to this situation was the infusion of large amounts of liquidity in order to be accessed by the banks that are in need of it. This liquidity will have medium term effects and having in mind the fact that economic growth in developed countries is expected to falter, it will ultimately lead to an increase in inflation.

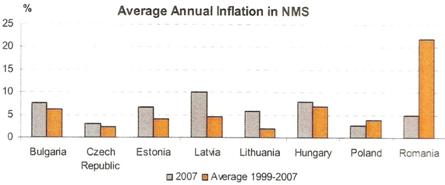

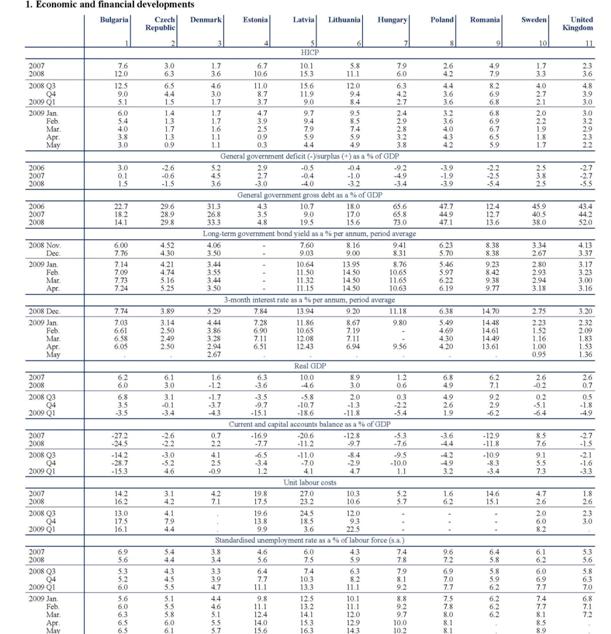

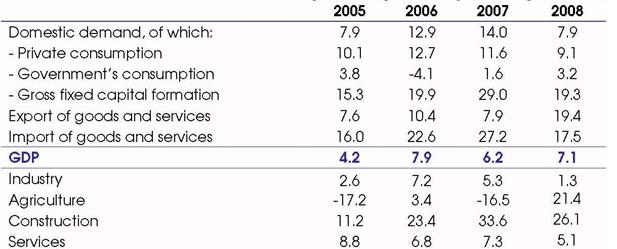

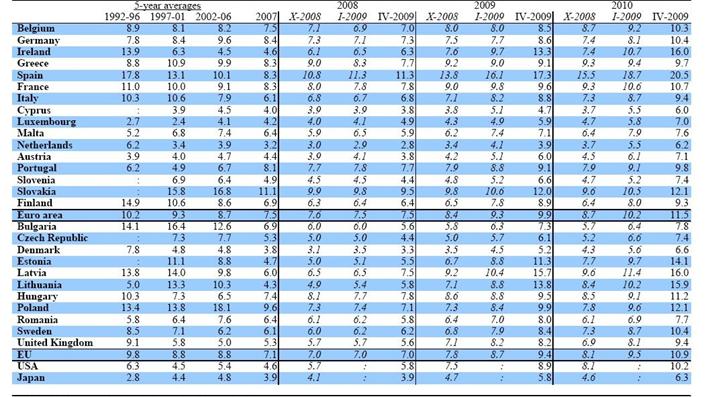

Table 3.1.: Average Annual Inflation in NMS

Source: Daniel Daianu, Laurian Lungu, 2009

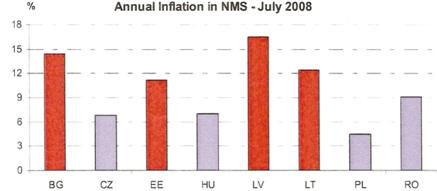

Table 3.2.: Annual Inflation Rate – July 2008

Source: Daniel Daianu, Laurian Lungu, 2009,

Analyzing

the two tables presented above we can observe that Bulgaria, the Czech

Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia managed to maintain a low

level of inflation in the 1999-2007 period, in spite of the fact that in the last year of the analysis all

countries faced a higher rate than the average. Table 3.2. shows that in July

2008, while the crisis’ effects have started to be felt inflation rates have

grown throughout the countries, but a notable observation is that the countries

that have a currency board arrangement have registered the highest rates.

Meanwhile, countries such as

Looking in more detail at Romania’s situation,

we can observe that it’s inflation has decreased spectacular in the last years

until the beginning of 2008, when it started growing, still, remaining at

considerably low level compared to the rest of the countries presented.

All throughout these

countries, the migration has brought about a shortage in labour. In the first

two quarters of 2009,

Overall, even on the

long term, countries with a floating exchange rate seem to have more to gain

from the latter. Currency board arrangements can be a viable short term

solution in the case of a high inflation but on the long term, especially when

the economy is going through a structural adjustment, most often it proves to

be costly. Furthermore, in the case that the country enters the MU in these

conditions, the fact that the exchange rate parity is not coordinated to the actual

macroeconomic fundamentals could lead to serious instability.

Specialists

consider that

The current financial crisis has lead to significant imbalances in the Romanian economy. This ultimately means that significant measures have to be taken in order to correct the problems at hand. Ever since the last quarter of 2008, there has been recorded a significant deceleration of activity and a drop in private capital flows, and furthermore, there is expected a fall in GDP by 4%. The Governments’ aim regarding this issue is that in 2011, the GDP will grow to reach 2.6%.

In order for

The Romanian Government should therefore struggle to correct the

excessive deficit by the year 2011, and therefore implement the fiscal measures

specified in the April 2009 budget most of all in the sector of public wages.

In this domain, there is a wrong approach applied. The government is

considering raising taxes so as to raise money, instead of focusing on cutting

back on expenses and encouraging economy. This could be a good anti-crisis

measure pending that it is a calculated and equilibrated measure. Still, the

analysis of the situation and the measures taken have to be well calculated and

every aspect and consequence taken into consideration. I say this having in

mind the EDP started by the European Commission in the case of

Furthermore,

the Government should seriously take into consideration the unemployment

benefit and the period of time it is granted for at least a short period of

time. Investments in infrastructure development should also be seriously

considered and applied as they offer workplaces to the unemployed and also

stimulate FDIs. In relation to this subject it is crucial to tackle the

delicate subject of undeclared employment and even more, offer tax exemptions

or lessening of the social contributions. Also the project “The First House” is a good initiative in spite of the

fact that, from my point of view, it is

not the one that will ultimately lead to the revival of the real estate market,

but rather the revival of the appetite of risk and investment of the citizens.

Financial stimulus in order to adapt to long term challenges also represent an

efficient manner in which the economy can be helped to rout the current

financial crisis. For example, stimulating the effectiveness of energy

obtaining and usage would prove to be a viable and beneficial long term

investment. Investment in research and education is a subject debated yearly in

In what regards public revenue, contrary to what the authorities are considering, I think that the decrease of the level of the VAT and income tax or at least their remaining at the current level is a better solution than their increase that inevitably leads to a higher level of inflation. The VAT is speculated to reach a level of 22% and the latter would go up 2% to reach 18% starting 2010. Also, as opposed to what in 2007 the prime-minister Tariceanu was considering, alongside the decrease in the VAT, the social contributions made by the employers to the public budget should decrease so as to sustain the maintaining of the current number of employees and even lead to the creation of new working opportunities for the unemployed. The Government seems to wish to correct the external disequilibrium and at the same time preserve the economic growth.

The absorption of EU funds could also

be a viable and efficient revenue source. Still, this depends on the quality of

the projects and plans prepared by the Government. In 2007 and 2008, EU would

have been able to offer up to 2.9 billion euro in structural funds, but the

Government only received a 1.85 billion euro advanced due to the fact that it

did not present credible and realistic projects. On the 7th July

2009, the Prime-Minister Boc in a press conference press specified that in

2007-June 2009,

Certain other measures that can prove to be useful in tackling the financial aspect of the current crisis are for instance the establishing of periodical meetings between bankers and the representatives of the business environment, the refraining of the authorities from the taxation of the reinvested profit in the case of any productive enterprise and the introduction of a credit moderator.

Predictions estimate that the current crisis will last up to 3 years, as Mr. Liviu Voinea stated in March this year. In this period, the Romanian Government has to take into consideration all the possible and efficient methods of exiting the current global economical and financial situation as unaffected as possible so as to be able to meet the entrance in the ERM-II on the 1st January 2012. In order for this to happen, in this period there have to be avoided inflationist measures that may benefit on the short run, but that can seriously affect the economy on the long run thus diminishing Romania’s capability of meeting the convergence criteria.

The current financial

and economic crisis has affected

continue imposing fiscal rules and implementing them through the creation of a fiscal council;

encourage the creation of workplaces from both the side of employers (through decreasing taxes) and that of the employees through solid investments in education and the stopping of undeclared employment;

increase the social benefit quota and the amount of time it is received;

investments in infrastructure will ultimately lead to the increase of FDIs and the creation of workplaces;

stimulate risk taking and investment from the general public and this can be done through the “First House” project;

decrease the level of VAT so as to encourage consumption;

focus on absorbing EU funds which represent an excellent source of revenue

offer virtual funds to banks

All these measures if implemented in a calculated manner ultimately lead to the resolving

of the major issues that stand in the way of meeting the convergence

criteria. The future perspectives of the euro zone indicate that it will become

the currency of the largest economic area. When

Comparing the

advantages and disadvantages, on the long run,

Will

Annex 1: Central Parity of the European Monetary System

+2,25%![]()

![]()

![]()

Source: Author

Annex 2 Macroeconomic and budgetary developments

Source: Daniel Daianu, Laurian Lungu, op. cit.

Annex 3 Annual Consumer Price Indexes and Inflation Rate (1971-2008)

|

YEAR |

CONSUMER PRICE INDEX-% |

INFLATION RATE-% |

YEAR |

CONSUMER PRICE INDEX-% |

INFLATION RATE-% |

Annex 4: Inflation Rate 2007-2008 within EU

|

Region |

Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

EU |

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

€-area |

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Top of Form |

|

|

|

Bottom of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Bottom of Form Top of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Top of Form Top of Form |

|

|

|

Bottom of Form Bottom of Form |

|

|

|

Annex 5: Developments outside the euro area

Annex 6: Total Harmonized Unemployment Rate – May 2009

Annex 7: Inflation Rate within the Euro Area

Annex 8: Budgetary Deficit / Surplus Euro Area

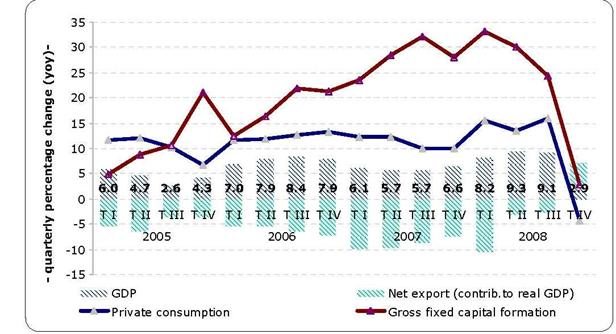

Annex 9: GDP

and its Main Components for

Source: Romanian Convergence Program May 2009

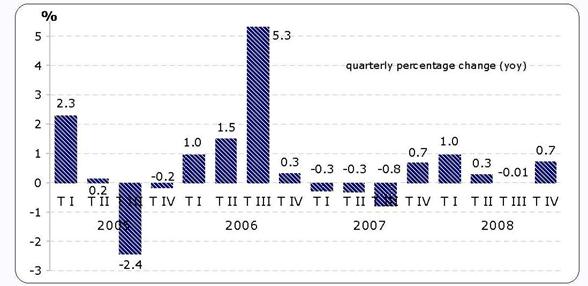

Annex 10: Evolution of Romanian GDP

Source: Romanian Convergence Program May 2009

Annex 11: Evolution of Romanian Employment

Source: Romanian Convergence Program May 2009

Annex 12: Evolution of the Unemployed

Number in 2007-February 2009

Annex 12: Evolution of the Unemployed

Number in 2007-February 2009

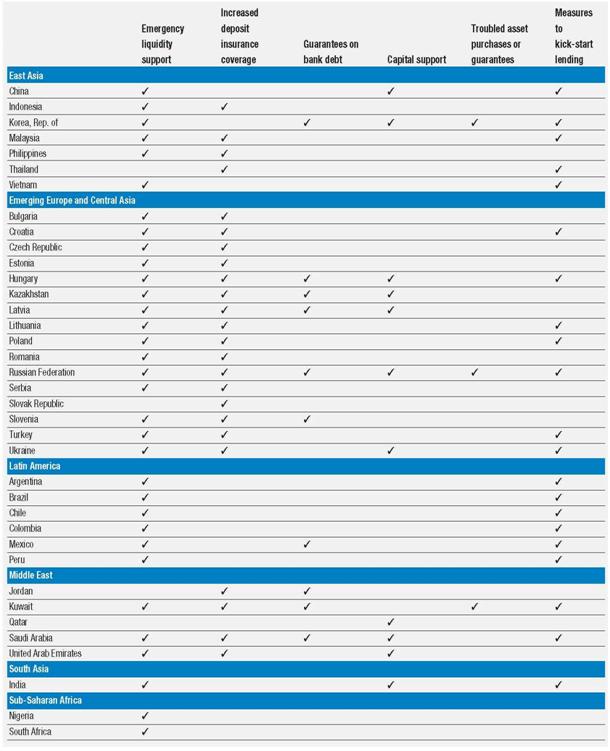

Annex 13: Crisis related policy measures announced by emerging economies by

April 2009

Annex 13: Crisis related policy measures announced by emerging economies by

April 2009

Source: Stephanou, Constantinos - “Dealing with the Crisis”, The World Bank Group, June 2009,

Annex

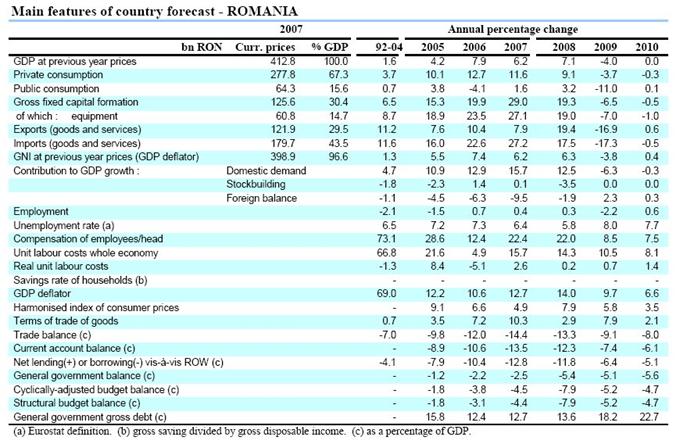

14:

Main Features of Country Forecast –

Annex 15: Romanian Gross Domestic

Product Volume (% change of proceeding year, 1992-2010)

Annex 15: Romanian Gross Domestic

Product Volume (% change of proceeding year, 1992-2010)

Alvarez, Gonzalez and Guéguen,

Daniel - “The euro:

Begg, Ian - ”Economic governance in an enlarged euro area”, Economic Papers311, European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Publications Brussels, March 2008

Breuss,

Fritz - “Stability and growth Pact. Experience and Future Aspects”, Springer

Science and Business

Breuss, Fritz - “Stability and growth Pact. Experience and Future

Aspects”, Springer Science and Business

Brociner, Andrew - Europa

Monetara. SME, UEM, moneda unica, Institutul European,

Commission

of the European Communities, “Report from the Commission for

Daianu, Daniel and Lungu, Laurian - “The Monetary

ECB Monthly Bulletin, 10th anniversary of ECB, 2008

European Central Bank, “ European Central Bank, the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks”, ECB Brochure, 2.1. “Structure and Task”

European Central Bank, “European Central Bank, the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks”, ECB Brochure, 2.3. “Tasks of the Eurosystem”

European Central Bank , “The European Central Bank. The Eurosystem. The

European System of

González-Páramo, José Manuel – Speech on “New Perspectives on Fiscal Sustainability”

Gros, Daniel and Mayer, Thomas and Ubide, Angel - “EMU at risk”, Centre for European Policy Studies, June 2005

Gündogdu, Burak and Girban,

Orkun - “

Hrebenciuc, Andrei and Zugravu, Paul - “EUROPEAN GOVERNANCE – THE STABILITY AND GROWTH PACT”, https://steconomice.uoradea.ro/ anale/volume/2008/v2-economy -and-business-administration/034.pdf

Isarescu,

Mugur – “Nine lessons from the current financial crisis”, Speech at the

Isarescu,

Mugur - “Probleme ale convergentei

reale in drumul spre euro”, Speech at the

Jarocinski, Marek - “Nominal and Real

Convergence in

Liviu, C. Andrei - “Euro” second edition, Ed. Economica, Bucuresti 2007

Nedelescu , Oana - “Avantajele si dezavantajele introducerii monedei unice europene”, 14.08.2008 Financiarul

Pelkmans, Jaques - “Integrare Europeana – Metode si Analiza Economica”,

2nd edition, European Institute of

Ravano, Emanuel - ”Euro Zone Divergences:” The “Noise” is Increasing”, July 2008

Russo, Massimo - “The Challenge of Economic

and Monetary Union: Lessons from

Sabau,

Cosmin - “THE REAL CONVERGENCE IN THE

CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES.THE CONVERGENCE PROGRAM OF

Scheller, Hanspeter K. - “The European Central Bank”, second revised edition 2006

Sibert, Anne - “Diverging

Competitiveness in the Euro area”,

Somers, Frans - “European Union Economies – a comparative study” 3rd Edition, Macmillan, 1998

Stephanou, Constantinos - “Dealing with the Crisis”, The World Bank Group, June 2009,

Tilford, Simon - “The euro at ten: Is its future secure?” January 2009, Centre for European Reform Essays

Tilford, Simon - “Will the eurozone crack?”, Centre for European Reform, 2006

Treaty of the European Union,

Valasek, Tomas - “What if the eurozone broke up?” 23rd March 2009,

*** “European Economic Policy”, The Economist, October 22nd 2002, https://www.economist.com/agenda/displayStory.cfm?Story_ID=E1_TQDNTDN

***“FMI spulbera orice iluzie: economia romaneasca va scadea cu 8%”, 7 July 2009, Ziarul Financiar,

***https://europa.eu/scadplus/glossary/stability_growth_pact_en.htm

***“Joseph

Stiglitz:

***“ Liviu Voinea: Criza va dura pana la trei ani”, 29.03.2009, Ziarul Financiar,

*** “Merrill Lynch:

The Non Member States are

Jaques Pelkmans , Jaques Pelkmans, “Integrare Europeana – Metode si Analiza Economica”, 2nd edition, European Institute of Romania, 2003, p. 24

“The European Central Bank, the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks”, ECB Brochure, 2.3. “Tasks of the Eurosystem”, p. 13

“The European Central Bank. The Eurosystem. The European System of

The national currencies ceased to be legal tender after a period of time that

differed from a member state to another. Even after this, central national

banks continued accepting the old currencies for different periods of time. The

first to become non-convertible are the Portuguese escudos (31 December 2002)

while

Oana Nedelescu , “Avantajele si dezavantajele introducerii monedei unice europene”, 14.08.2008 Financiarul, www.financiarul.ro

Daniel Daianu and Laurian Lungu, “The Monetary

Marek Jarocinski, “Nominal and Real Convergence in

Anne Sibert, “Diverging Competitiveness

in the Euro area”,

Massimo Russo, “The Challenge of Economic and Monetary Union:

Lessons from

Mr. Carlo Azeglio Ciampi was Treasury Minister in the Italian Government from April 1996 to March 1999.

Daniel Gros, Thomas Mayer, Angel Ubide, , “EMU at risk”, Centre for European Policy Studies, June 2005

Gonzalez Alvarez, Daniel Guéguen, “The euro:

Simon Tilford, “The euro at ten: Is its future secure?” January 2009, Centre for European Reform Essays,

Tomas Valasek, “What if the eurozone broke up?” 23rd March 2009, https://centreforeuropeanreform.blogspot.com/

Milton Friedman (July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American liberal economist, statistician and public intellectual, and a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

Fritz Breuss, “Stability and growth Pact.

Experience and Future Aspects”, Springer Science and Business

“The European Central Bank. The Eurosystem.

The European System of

Speech by José Manuel González-Páramo, Member of the Executive Board of

the ECB

Conference on “New Perspectives on Fiscal Sustainability”

Iain Begg, “”Economic governance in an enlarged euro area”, Economic Papers311, European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Publications Brussels, March 2008

Cosmin Sabau, “THE REAL CONVERGENCE IN THE CENTRAL AND

EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES.THE CONVERGENCE PROGRAM OF

Isarescu, Mugur - “Probleme ale

convergentei reale in drumul spre euro”, Speech at the

|

Politica de confidentialitate |

| Copyright ©

2026 - Toate drepturile rezervate. Toate documentele au caracter informativ cu scop educational. |

Personaje din literatura |

| Baltagul – caracterizarea personajelor |

| Caracterizare Alexandru Lapusneanul |

| Caracterizarea lui Gavilescu |

| Caracterizarea personajelor negative din basmul |

Tehnica si mecanica |

| Cuplaje - definitii. notatii. exemple. repere istorice. |

| Actionare macara |

| Reprezentarea si cotarea filetelor |

Geografie |

| Turismul pe terra |

| Vulcanii Și mediul |

| Padurile pe terra si industrializarea lemnului |

| Termeni si conditii |

| Contact |

| Creeaza si tu |